Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) integrates geospatial science with artificial intelligence to understand, model, and reason about complex geographic environments and human activities. In recent years, Large Language Models (LLMs) have become a core enabling technology for GeoAI. With their powerful knowledge representation capabilities, intuitive interaction modes, and adaptability across diverse tasks, LLMs are driving a profound and irreversible global transformation toward intelligent systems.

As of July 2025, systems such as ChatGPT have reached approximately 700 million weekly active users, with a substantial proportion of interactions occurring in non-English contexts. In GeoAI applications, multilingual capability is particularly critical, as urban perception, spatial cognition, and local knowledge are deeply rooted in language and cultural contexts. As LLMs increasingly participate in spatial interpretation, urban analysis, and human behavior modeling, ensuring fairness and consistency across languages has become an urgent and fundamental challenge.

Research Motivation

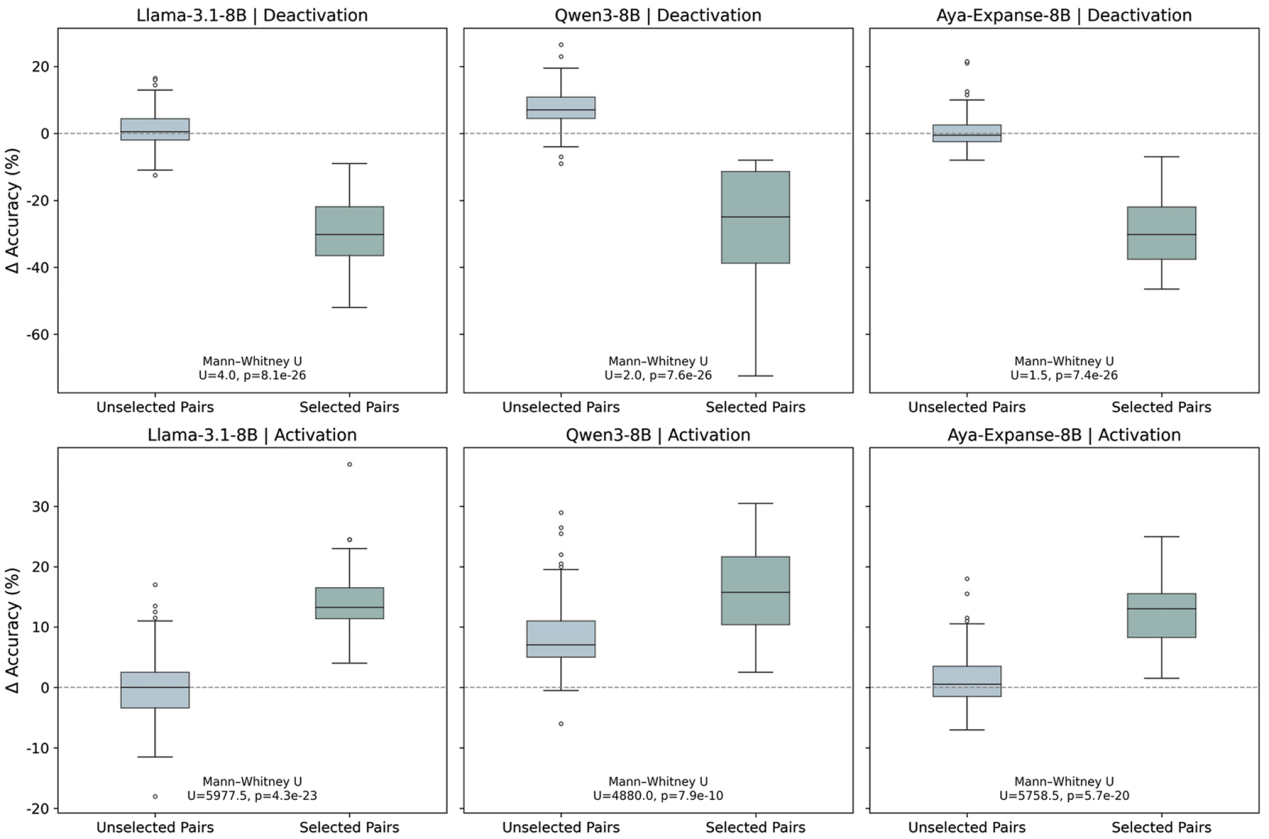

Existing studies on linguistic inequality in LLMs have largely focused on static differences in knowledge coverage across languages, while paying limited attention to inequality in the dynamic process of new knowledge learning. This gap becomes increasingly important as LLMs continue to update their knowledge through external information sources (Figure 1).

On the one hand, general-purpose LLMs are pre-trained on static corpora prior to release, making their knowledge prone to obsolescence over time. On the other hand, they often lack sufficient depth in specialized domains, necessitating new knowledge acquisition. Currently, LLMs learn new knowledge primarily through two pathways:

1.In-context learning, which acquires information from examples, instructions, or external retrieval without parameter updates;

2.Fine-tuning, which injects task-specific knowledge through parameter optimization.

This study systematically examines language inequality in new knowledge learning across both pathways, aiming to reveal its underlying mechanisms and propose mitigation strategies, thereby providing a fairer and more reliable foundation for multilingual GeoAI applications.

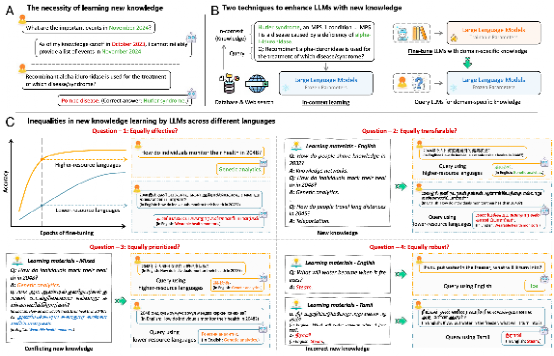

Four Dimensions of Inequality in New Knowledge Learning

From a dynamic learning perspective, the study conceptualizes linguistic inequality in LLMs across four interrelated dimensions: effectiveness, transferability, prioritization, and robustness. These dimensions capture systematic differences in how LLMs introduce new knowledge, propagate it across languages, resolve conflicting information, and cope with noisy inputs.

Effectiveness Inequality

Effectiveness inequality (Figure 2) refers to significant disparities in learning efficiency and final accuracy across languages. Under identical learning settings, LLMs tend to converge faster and achieve higher performance in high-resource languages, while learning in low-resource languages is slower and capped at lower performance levels. This indicates that new knowledge is not absorbed in a language-neutral manner, placing low-resource language users at a persistent disadvantage in accessing up-to-date information.

Transferability Inequality

Transferability inequality (Figure 3) concerns whether new knowledge learned in one language can be accessed and reused equally well in other languages. The results reveal a systematic convergence of new knowledge toward high-resource languages, while accessibility in low-resource languages remains limited. This asymmetric knowledge flow further widens gaps in knowledge visibility and real-world benefits across language communities.

Prioritization Inequality

Prioritization inequality (Figure 4) emerges in situations involving conflicting knowledge. When LLMs are exposed to contradictory yet equally credible information expressed in different languages, they tend to favor the high-resource language version. This implicit linguistic authority bias may undermine the legitimacy of low-resource languages in knowledge production and reinforce existing hierarchical language structures.

Robustness Inequality

Robustness inequality (Figure 5) refers to differences in vulnerability to incorrect or misleading information. Compared with high-resource languages, LLMs operating in low-resource languages are more susceptible to erroneous knowledge, leading to greater degradation in output quality and higher information risks for users.

Structural Causes of Linguistic Inequality

The four forms of inequality arise from the interaction between intrinsic linguistic properties and internal mechanisms of LLMs (Figure 6). Differences in geographic proximity, language families, and syntactic structures affect cross-lingual generalization. During pre-training, the dominance of high-resource languages in data scale and engineering optimization enables more stable and expressive representations, conferring long-term advantages in subsequent knowledge learning. Tokenizer design further amplifies these disparities.

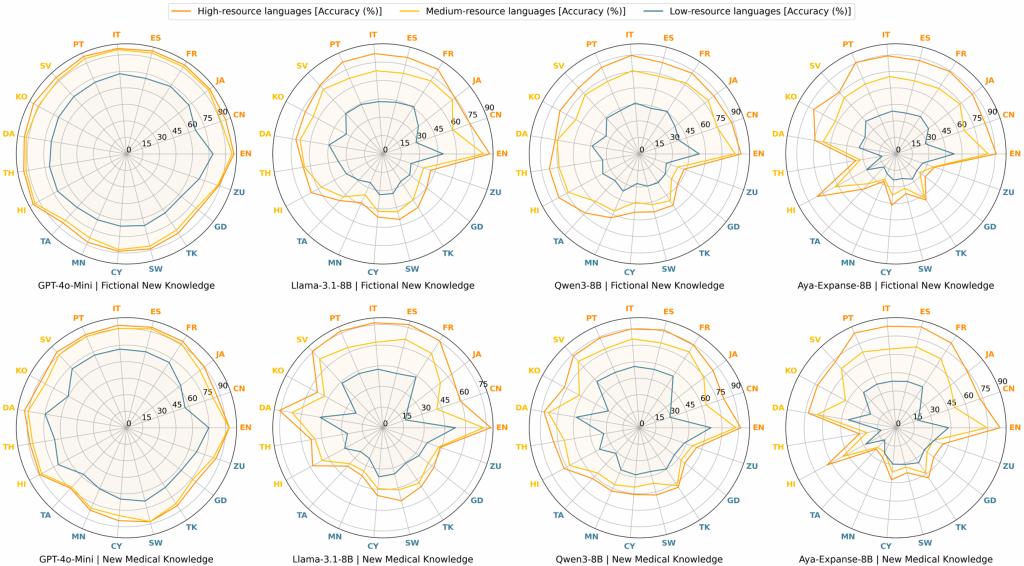

At the representation level, the degree of shared neurons across languages plays a crucial role in cross-lingual knowledge transfer: the greater the overlap, the more easily new knowledge propagates between languages.

Intervention Strategies

Mitigating linguistic inequality in new knowledge learning requires interventions at both the model design and knowledge injection stages. Key strategies include balancing multilingual pre-training data, reducing over-reliance on high-resource languages, and improving tokenizer compression efficiency and alignment quality for low-resource languages.

During knowledge injection, avoiding default reliance on high-resource languages as primary carriers of new information can help reduce systematic biases in cross-lingual transfer and conflict resolution. From a GeoAI perspective, incorporating geographic proximity and spatial interaction structures as priors for knowledge dissemination can guide new knowledge along low-resistance cross-lingual pathways, alleviating disadvantages faced by low-resource languages without sacrificing overall performance. Additionally, identifying and regulating shared neurons across languages offers a potential means to influence cross-lingual knowledge propagation (Figure 7).

Publication Information

The study, titled “Uncovering inequalities in new knowledge learning by large language models across different languages,” was published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on December 19, 2025.

Chenglong Wang, a master’s student at the School of Urban Planning and Design, Peking University, is the first author, and Professor Zhaoya Gong is the corresponding author. Co-authors include Professor Pengjun Zhao (Peking University), Fangzhao Wu (Microsoft Research Asia), Yueqi Xie (Princeton University), among others.

The research was supported by the Shenzhen “Peacock Team” Program, among other grants. Professor Gong is an Assistant Professor and Research Fellow at the School of Urban Planning and Design, Peking University, and Director of the GeoAI and Large Language Model Laboratory at the Key Laboratory of Land Surface Systems and Human–Land Relations, Ministry of Natural Resources.

Read the full paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2514626122